Elk Translocation Program on Vancouver Island Aims to Restore Roosevelt Elk to Their Former Range

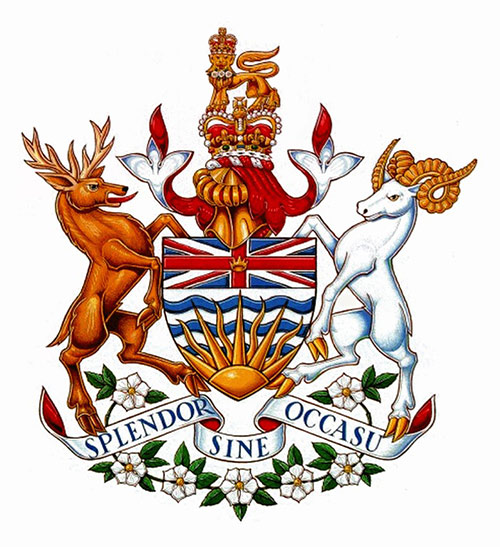

BC’s magnificent wildlife has long formed part of our province’s identity. Take the provincial Coat of Arms: while other Western provinces have chosen to include the likes of lions and unicorns into their designs, a pair of iconic ungulates make up BC’s provincial emblem. On the right, a bighorn ram represents the wildlife of the mainland. On the left, a rather wild-looking Roosevelt elk symbolizes Vancouver Island.

The Roosevelt is a fitting representative for the Island: it remains a stronghold for this species whose range was severely reduced following the arrival of the Europeans in the mid-19th century. Though Roosevelts remain on BC’s list of species of concern, populations in some areas of the Island are thriving, to the point where conflicts are arising between humans and herds.

On the Island’s east coast, near the village of Sayward, the Salmon River watershed is ideal habitat for elk. The moist, rich soils of the river’s floodplain produce optimal forage for Roosevelts, both in the form of native plant species and agricultural crops. This vegetational bounty has allowed elk numbers to increase to the point where herds have become a nuisance for local residents. Crop predation and highway collisions are of primary concern, and elk have also been known to browse nearby forestry plantations. Having a local overabundance of a highly-valued species of concern presents an interesting challenge – and opportunity. Rather than focussing their efforts on culling the herd, wildlife managers have chosen to spread the wealth, so to speak, by moving some of Sayward’s surplus elk to wilderness areas where Roosevelts once roamed.

Wildlife biologist Billy Wilton works for the B.C. Government, helping develop and implement the Roosevelt Elk management plan. The plan aims to increase the elks’ numbers in ranges where ecological conditions are suitable. He also spent four years working with the Government’s senior Roosevelt elk specialist, Darryl Reynolds on the Lower Mainland Roosevelt elk recovery project. Through ongoing financial support from organizations such as the Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation, this project has achieved a significant increase in the number of elk on the South Coast. Of the 25 wilderness areas identified as candidates for Roosevelt reintroduction in 2000, 19 have been successfully repopulated. By transporting elk from nuisance herds on the Sunshine Coast to these prime habitat areas, the lower mainland Roosevelt population has grown from an estimated 315 animals in 2000 to approximately 1600 individuals in 2015, an increase of more than 500%. These impressive results have inspired Wilton and his colleagues to continue elk translocations on the Island.

“I’ve been really fortunate to work with Darryl and learn from his experiences,” says Wilton. “We work really hard to minimize the stress on the animals, and we’ve fine-tuned the process to protect both the elk and people involved.”

Wilton says the first step is to identify a suitable herd of “nuisance” elk, composed primarily of pregnant cows in order to boost the reproductive potential of the herd. Then, the team set up a portable chain-link corral in an area known to be frequented by the target herd so that they become comfortable with its presence. Once winter sets in, the trap will be baited with a tempting combination of alfalfa, grain, and molasses, along with some minerals to keep the animals healthy.

“We wait until the elks’ natural food sources start to dry up before trying to entice them with bait,” says Wilton. “Waiting until winter also helps ensure the bears are asleep, as we like to avoid accidently feeding any large carnivores.”

Last year, Wilton and his colleagues trapped and transferred twenty-four nuisance elk from the Sayward area to the Mahatta River population unit west of Port Alice. The project went off without a hitch, and Wilton and his team are eager to repeat the translocation process. Plant communities in the release locations are similar to those in the Salmon River area, but the habitat is not as suitable, making it highly unlikely that the transplanted herd will increase to the levels seen in Sayward. The goal is to establish a sustainable population that will both benefit the ecology of the area and allow for some opportunities for harvest.

“Reintroducing elk to their historic range helps restore biodiversity,” says Wilton. “They’re a piece of the puzzle that went missing. Roosevelts are large, generalist grazers, so taking them out of the system impacts plant composition and has implications for a whole range of species.”

In addition to their influences on habitat, Roosevelts are an important prey species for wolves, cougars, and even black bear. They are also highly valued by hunters and First Nations. Each year, the province receives around 16,000 applications for just 250 Limited Entry Hunt Authorizations for Roosevelt Elk on Vancouver Island, and First Nations harvest around the same number annually. Both groups are eager to see populations return to historical levels, and are willing to assist in making it happen.

“Last year, we talked with the Quatsino First Nation [whose territory the elk will be released in], and they expressed an interest in helping us with the project,” says Wilton. “We also had a really dedicated group of guys from the Sayward Fish & Game Association working with us on the Mahatta River translocation last winter. They were out there every day, baiting the trap, monitoring the cameras, maintaining the equipment – we really couldn’t do this project without the help of the volunteers.”

A remote camera captures an image of a bull looking rather relaxed inside a temporary elk trap near Sechelt, BC. Biologists set up and bait the corrals well before the planned capture date to get the target herd comfortable with its presence.

A remote camera captures an image of a bull looking rather relaxed inside a temporary elk trap near Sechelt, BC. Biologists set up and bait the corrals well before the planned capture date to get the target herd comfortable with its presence.

While there are no guarantees that elk translocations will result in increased hunting opportunities, the results from the Lower Mainland project are certainly encouraging. Project leader Darryl Reynolds estimates that nine out of ten translocations from that project have resulted in new hunting opportunities, usually within five years of the release.

“The Limited Entry Hunting opportunities we have on the South Coast today can be directly attributed to the success of the Elk Recovery program,” says Reynolds. “Without it, there wouldn’t be any hunt.”

Wilton agrees that five years is a reasonable time frame when forecasting potential new harvest opportunities. “Putting 20-25 elk in an area really makes a big difference in terms of the recovery of that population. Their numbers tend to increase quite quickly. We’ll be working with First Nations and stakeholders to evaluate if and when the population can sustain a harvest: we certainly don’t open it up just because it’s been five years, but that’s been our experience in many other areas.”

To keep tabs on how the population is doing, the project team will be conducting helicopter surveys in the spring of each year, as well as using strategically-placed GPS and radio collars.

“Elk differ from most other North American ungulates in that they are social herd animals,” says Wilton. “Matriarchal herds have a lead cow and a couple of other elders that hold knowledge about how to find food, water, and what to watch out for on the landscape. These are the cows we’ll be trying to collar.”

The GPS collars send regular emails to the biologists with information about their locations and habitat use. They also send out a mortality signal if the animal stops moving for 8 hours, hopefully giving the project team a chance to investigate the cause of death before scavengers move in.

“Understanding mortality is important for our management of these herds, and previously it was very difficult to get this information in real time,” says Wilton. “The collars also help us reduce survey helicopter costs by pinpointing the herd’s location.”

Only time will tell if Wilton’s elk relocation project is successful in establishing herds robust enough to provide additional harvest opportunities on Vancouver Island. Regardless, working to restore the iconic Roosevelt to its former range is laudable from an ecological perspective, and an initiative the hunters of British Columbia can be proud to support through surcharges on their licence purchase.