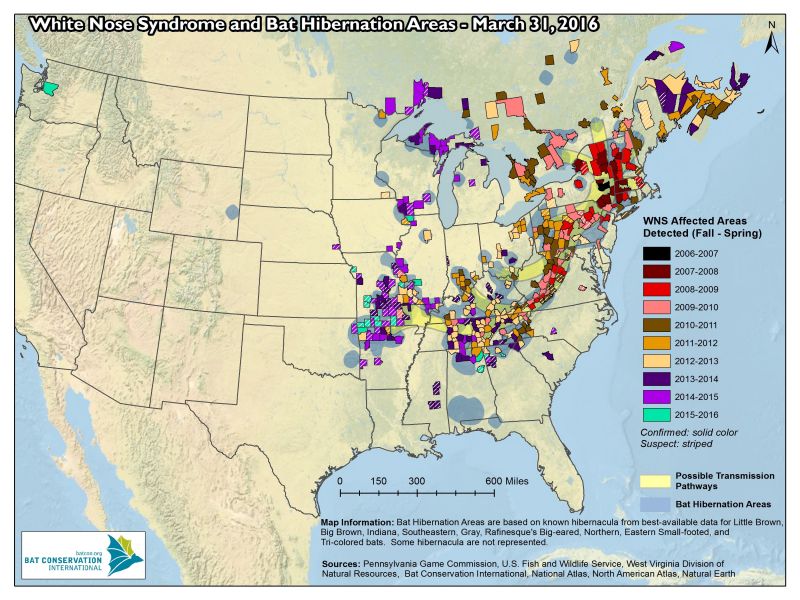

The BC Community Bat Program, in collaboration with the Province of BC, is on the lookout for signs of White-Nose Syndrome (WNS). Fortunately for the bats of BC, it has been a quiet winter. WNS is a fungal disease harmless to humans but responsible for the deaths of millions of insect-eating bats in eastern North America. WNS was first detected in Washington State in March 2016. To monitor the spread of this disease, Community Bat Program coordinators have been collecting reports of unusual winter bat activity across southern BC and ensuring that dead bats are sent to the Canadian Wildlife Health Centre lab for disease testing. To-date, no WNS has been reported in the province.

But spring conditions mean increased bat activity – and an increased chance of detecting the disease. As bats begin to leave hibernacula and return to their summering grounds, our chances of seeing live or dead bats increases, and the Community Bat Program is continuing to ask for assistance.

“We are asking the public to report dead bats or any sightings of daytime bat activity to the Community Bat Project (CBP) as soon as possible (1-855-922-2287 ext 24 or info@bcbats.ca)” says Mandy Kellner, coordinator of the BC Community Bat Program. Reports of unusual bat activity will help focus research, monitoring and protection efforts.

Never touch a bat with your bare hands as bats can carry rabies, a deadly disease. Please note that if you or your pet has been in direct contact with a bat, immediately contact your physician and/or local public health authority or consult with your private veterinarian.

Currently there are no treatments for White Nose Syndrome. However, mitigating other threats to bat populations and preserving and restoring bat habitat may provide bat populations with the resilience to rebound. This is where the BC Community Bat Program and the general public can help. Funded by the Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation, the Province of BC, and the Habitat Stewardship Program, the BC Community Bat Program works with the government and others on public outreach activities, public reports of roosting bats in buildings, and our citizen-science bat monitoring program.

To contact the BC Community Bat Program, see www.bcbats.ca, email info@bcbats.ca or call 1-855-922-2287 ext. 24.

Our thanks to the BC Community Bat Program for this update.

HCTF is providing funding for the BC Community Bat Program through grants to project 0-476, Got Bats? B.C. Community Outreach, Conservation and Citizen Science Project