The November rut is a magnificent display of strength and agility, a refined ritual that has been practiced by bighorns for centuries. The sights and sounds of these iconic B.C. mammals vying for dominance evoke a sense of respect for the ruggedness of a species that Theodore Roosevelt referred to as “one of the noblest beasts”.

Yet the rut can be a treacherous time for bighorns, far beyond the risk of injury from their intra-species tussles. For these highly social animals, the real danger can lie with the company they keep.

Wild sheep share a number of similarities with their domestic cousins: they will use the same forage and water sources, and can even interbreed. Where bighorn range and domestic sheep operations overlap, it’s understandable that a randy ram might find a large flock of domestic ewes worth a closer look. Unfortunately, these forays can have deadly consequences. Even nose-to-nose contact between the two species can result in the transfer of a pathogen lethal to wild sheep. And because it takes time for animals to become symptomatic, an infected (but visibly healthy) bighorn that returns to its herd will spread the disease, potentially decimating an entire population.

For nearly a century, domestic sheep interactions were a suspected cause of bighorn die-offs, and the disease transfer mechanism was irrefutably confirmed through marked protein experiments in 2010. The culprit was found to be Mannheimia haemolytica, a pneumonia-causing bacterium commonly carried by domestic sheep. Domestics have evolved resistance to this particular strain and rarely show symptoms, but wild sheep are highly susceptible and often die within days of contracting it. In B.C., mass bighorn die-offs have been documented since the early 1900s, with the last major die-off occurring in the Okanagan in 1999. M. haemolytica-induced herd mortalities have occurred in the United States as recently as August of 2013.

Provincial wildlife veterinarian Dr. Helen Schwantje is no stranger to the issue: she began studying disease transfer from domestic to wild sheep as part of her Master’s thesis in the 1980s. Since then, she has witnessed many developments in the science used to pinpoint the pathogens causing die-offs, but says researchers still haven’t come up with a silver bullet. “We haven’t developed effective vaccines to prevent these deaths in bighorns, nor do we have an effective method of delivering vaccines to these wild animals,” Schwantje says. “In the absence of a medical solution, wildlife agencies in North America recommend that wild and domestic sheep populations be completely separated to avoid disease transmission.”

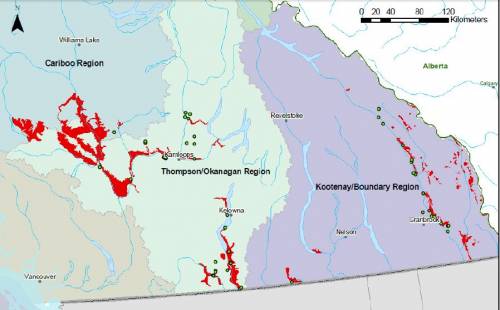

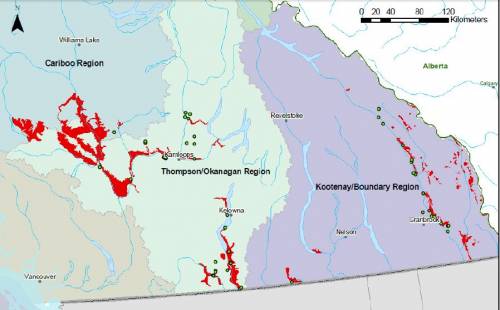

Schwantje was one of the original architects of the B.C. Sheep Separation Program, developed in response to pneumonia die-offs in the East Kootenay. The program aims to achieve effective separation between the two species through education, stakeholder consultation, policy development and on-the-ground action. The Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation has supported the Sheep Separation Program for nearly a decade, and in more recent years, the Foundation has funded the program’s provincial coordinator position. Jeremy Ayotte took on the role in July, and is already working hard to move the program forward: “Shortly after I started the job, I put out an invitation to bring together some of the stakeholders, both to introduce myself and to provide a forum to exchange ideas. The response was amazing. The Wild Sheep Working Group is made up of a real diverse bunch of participants: domestic sheep producers, regional biologists, hunters… a great group of passionate, knowledgeable people wanting to work towards a solution.

“We really want to take a positive approach- a collaborative approach – rather than running around placing blame.”

Ayotte is already exploring innovative ways to allow and encourage sheep farmers to provide effective separation between their flocks and wild sheep. Traditional management plans have focused on creating buffer zones and the use of non-contact fencing, but these methods have drawbacks: buffer zones require large tracts of land (impractical on smaller agricultural properties), and double-fencing entire pastures is expensive and can interfere with wildlife migration patterns.

“One of the new management techniques we’re exploring is the idea of a refuge pasture: this would be a smaller, fenced field within a larger pasture that farmers could place their sheep in if bighorns are spotted nearby, or during times where there’s a high risk of contact, such as during the rut,” Ayotte explains. His team is also looking at potentially starting a certification program to recognize lamb producers following separation management guidelines, along the same lines as dolphin-friendly tuna. “A positive marketing angle such as “bighorn-friendly” lamb would also be a great way of increasing awareness of this issue,” says Ayotte. “I think the program’s done a good job of educating commercial producers, especially in high-risk areas, but there’s still some work to be done with small-scale landowners, who might want a couple of lambs for vegetation control or 4-H purposes. Even a single sheep in a high-risk area can pose a danger to bighorns”.

Ayotte is also working to consolidate data on program projects, sheep farming operations, and bighorn herd information so that it is kept accessible and current.

“There’s a lot of valuable data out there, collected by regional wildlife biologists and through citizen science: we’ve got great Rod & Gun Club support in many areas, where folks are annually conducting on-the-ground counts and recording any observation of sickness in the herd. Prior to receiving the funding for this coordinator position, the program didn’t have the capacity to consolidate that data and use it effectively. Now, we’re looking at ways of utilizing it to improve effective separation. We’ve had a wonderful tool donated to us by the US Forest Service that has been specifically designed to identify the highest risk areas based on knowledge of sheep habitat and behaviour, so we can focus our resources on them.” Ayotte expects these areas will coincide with ones already identified, but he thinks having a science-based tool might go a long way in getting policy in place to prevent additional domestic sheep operations from starting up in bighorn territory.

Achieving any sort of protection through policy has so far proven a difficult road: in the Okanagan and the Kootenays, sheep farming is well established, and previous attempts at using covenants and by-laws to restrict farming activity have had little effect due to ALR rules and the Right-to-Farm Act. There is, however, one area where Ayotte and his colleagues feel legislation could play a very important role: B.C.’s North, home to a significant portion of the world’s thinhorn sheep populations. “These sheep have never been in contact with domestics,” says Ayotte. “It’s chilling to think how potentially devastating this disease could be if that contact occurs.

“It’s a tough question: how much time and resources should we put into southern areas of the province where the disease is already established, versus working on preventative measures for the untouched populations of North?”

Managing livestock/ wildlife conflicts on private land is a daunting task, and the program will need to continue to foster innovation and collaboration in order to find effective solutions. But with challenge comes opportunity. “One of our goals is to monitor the different strategies we’re trialing, and then share our success stories, within the province and beyond,” Ayotte reflects. “Historically, the program’s had its ups and downs, but now that we’ve got some stability through funding, there’s a perceivable buzz: you can really feel the momentum starting to pick up.”

Additional Resources:

For more information on the BC Sheep Separation Program, contact Program Coordinator Jeremy Ayotte on 250-804-3513 or email jeremy.ayotte@gmail.com

Websites:

Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agency’s Wild Sheep Working Group: This joint US-Canada association is a partner of the BC Wild/Domestic Sheep Separation Program, and their site provides information and links to resources about wild sheep management.

Wild Sheep Society of BC: an organization dedicated to promoting and enhancing wild sheep and wild sheep habitat throughout British Columbia.

Publications:

Domestic and Wild Sheep: Reducing the Risk of Disease Transfer Note: This brochure is currently undergoing a refresh, and the updated copy will be posted when available

Managing Wild and Domestic Sheep: A detailed report on Managing the Risk of Disease Transfer between Wild and Domestic Sheep in the Southern Interior of BC

To report a wild and domestic sheep/goat interaction, use the RAPP line.

At M.V. Beattie, the $3,200 PCAF grant is helping change a wet “problem area” on the school grounds into a replica of Shuswap River, and will become a place where students can study wetlands. Retired principal and outdoor activist Kim Fulton (aka Dr. Fish) has been helping M.V. Beattie with this project. He explains wetlands are one of the most threatened, undervalued, and misunderstood ecosystems in B.C. By re-creating a wetland system on the playground, classes will study its evolution, and come to know its beauty and ecological benefits. Hopefully, present and future decision makers will be better equipped to make informed choices for fish and wildlife. Principal Denise Brown says that, in future, a solar powered waterfall will be added into the existing wetland. “The movement of the water is important to the environment and the aesthetic value will be appreciated by our students and the community in general. Often the children spend their break times in the wetland exploring and watching nature.”

At M.V. Beattie, the $3,200 PCAF grant is helping change a wet “problem area” on the school grounds into a replica of Shuswap River, and will become a place where students can study wetlands. Retired principal and outdoor activist Kim Fulton (aka Dr. Fish) has been helping M.V. Beattie with this project. He explains wetlands are one of the most threatened, undervalued, and misunderstood ecosystems in B.C. By re-creating a wetland system on the playground, classes will study its evolution, and come to know its beauty and ecological benefits. Hopefully, present and future decision makers will be better equipped to make informed choices for fish and wildlife. Principal Denise Brown says that, in future, a solar powered waterfall will be added into the existing wetland. “The movement of the water is important to the environment and the aesthetic value will be appreciated by our students and the community in general. Often the children spend their break times in the wetland exploring and watching nature.”