It could be the plot for a science fiction horror movie. A disease that reduces the brain to Swiss cheese, spreads insidiously, is always fatal, and is caused by something that is difficult to kill because it is not actually alive. Yikes! This is Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD). It is a disease of cervids (animals in the deer family), and in Canada in the wild, it has been identified most commonly in mule deer, but also in white-tailed deer, elk and moose. Recently CWD has been reported in wild reindeer in Scandinavia, so our caribou populations are also potentially at risk.

CWD is one of a group of diseases called Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy that affect the brain and nervous system of many animals including humans, cattle and sheep. The disease agent is most likely an abnormal form of protein called a prion (the acronym for proteinaceous infectious particle only). Why a protein becomes a prion is not known. Proteins are normal organic molecules of healthy cells in all living creatures. However, in an animal with CWD, contact with prions causes normal proteins to change shape, then go rogue and become deadly. These altered proteins so resemble normal ones that they are not destroyed by the animal’s immune system. In certain areas of the brain, the accumulation of these abnormal proteins kills cells, so that that part of the brain looks “spongy”. As the disease progresses, body functions associated with those areas of the brain begin to fail. An affected animal gradually loses weight, becomes listless, may salivate heavily and urinate frequently. The animal eventually wastes away (hence the disease name) and dies. However, the prions in excreted body fluids and feces (and some body parts once the animal dies) may persist in the soil and be taken up by growing plants. This is a unique feature of CWD. Then, healthy animals that eat such vegetation can become infected. Even transporting feed or hay grown on land where CWD has been present can spread the disease.

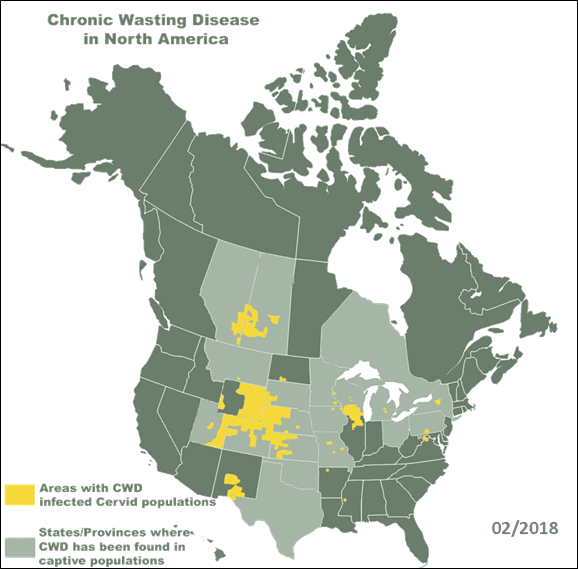

CWD is well established on game farms and in wild deer in much of central USA. In Canada, so far the disease is reported only in Alberta and Saskatchewan in farmed and wild deer and elk, but in 2018, CWD was recognized on a red deer farm in Quebec. The CWD Alliance website is a good source for more information.

Monitoring for CWD in BC began in 2001 and fortunately no samples have tested positive. This is partially attributable to Provincial regulations that prohibit the farming of native cervids or importing live cervids. Recent additional regulations prohibit the importing CWD risky body parts of deer harvested outside the Province, and possessing scents derived from cervids. However, there is no room for complaisance. The Alberta CWD Program has mapped the disease expanding slowly but relentlessly westward, especially following the valleys of the South Saskatchewan, Battle and Bow Rivers. In 2017, CWD cases were reported very near to both Calgary and Edmonton. In addition, recent cases in Montana mean that BC is becoming surrounded by a growing risk of CWD.

From CWD Alliance

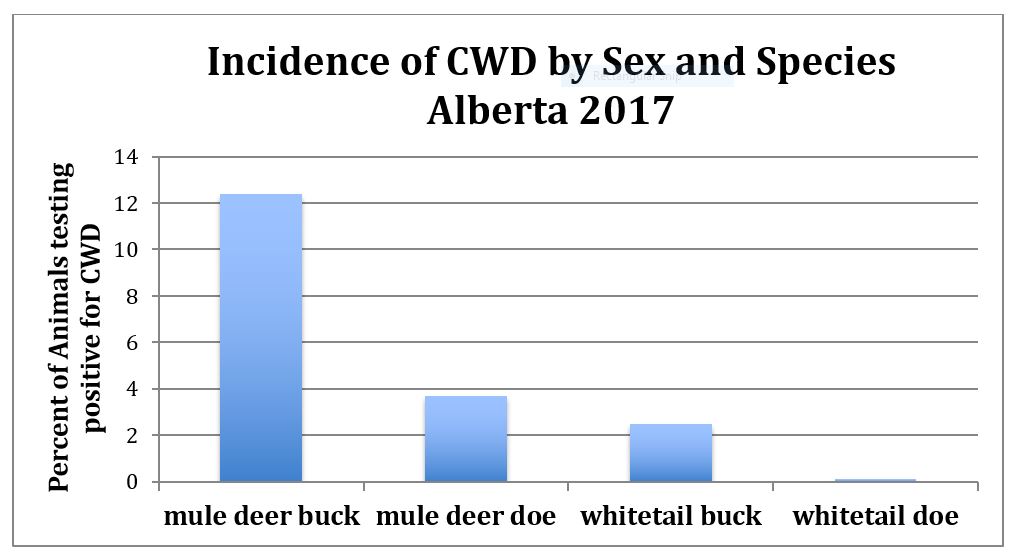

Some of BC’s most cherished game animals are at risk, but the disease does not affect all animals equally. In Alberta, it is mule deer that are most susceptible, while in other jurisdictions it is white-tailed deer or elk. In 2017, the Alberta Government tested for CWD in 6,340 wild deer and elk. The disease was detected in 8.2% of mule deer, 1.8% of white-tailed deer and 0.4% of elk samples (so far the only recorded incidence in Alberta moose is a single positive in 2012). Males are more likely to be infected than females. Since 2005, CWD has been detected in 796 Alberta mule deer, 119 white-tailed deer, two elk and one moose. To obtain these samples, the Alberta Government CWD Surveillance Program “relies heavily on participation by hunters, guides and landowners”.

In BC, the increasing proximity of the disease to the Province’s eastern border and the low number of samples from the Peace Region (7B) has increased the urgency for improved monitoring. In 2018, the Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation (HCTF) and partners contributed funding to improve CWD surveillance in the Peace. Most of the HCTF funding comes from the surcharge on hunting, fishing, trapping and guide outfitting licences sold in BC. This money is used to fund conservation projects benefitting wildlife and fish populations, beyond the basic management by governments.

BC’s Wildlife Veterinarian, Dr. Helen Schwantje, said, “The Peace is considered the Region at highest risk of natural expansion of CWD from Alberta into British Columbia and hunters have a key role in helping to avoid this disease from entering our Province”.

An objective of the HCTF-funded project is to increase by 10 times the number of samples from Peace Region from less than 30 to at least 300 annually. To test for CWD, the whole head of the suspect animal is required. One of the best ways to gather such samples is to involve hunters.

“Hunters are probably the group that should be the most concerned about the spread of CWD ”, says CWD Project coordinator Brian Paterson, “And coincidentally, they are the group that can help the most with early detection efforts by submitting the heads of harvested animals to our program.” Paterson continues, “As outreach coordinator, it is my role to spread information, increase awareness, and let hunters know how important the submission of a single head is in the fight against CWD.”

In 2018, Paterson delivered information on CWD to hunters in the Peace Region through contact with sportsmen’s groups, outdoor sports equipment stores, trappers, meat cutters as well as interviews on CBC and via social media sites like Facebook.

In the first year, Paterson says the response to the project has been really good, but he wants to continue the outreach and recruitment, so that “Submission of heads becomes part of the hunt. If you know that your buddies are submitting heads, you are more likely to do the same. The program can’t be truly effective without hunter participation”.

Awareness and cooperation are key, but with a sample as large as a whole head, getting to a collection site (such as dedicated freezers) must also be convenient. The locations of collection sites and a summary of the results of CWD testing will be posted on the BC Wildlife Health CWD website (www.gov.bc.ca/chronicwastingdisease.ca). If any samples test positive, the hunter will be contacted directly and confidentially.

To date, there is no treatment for affected wild animals and no vaccine, so prevention is key. The risk to BC’s game animals is real and the consequences potentially dire, but hopefully the science fiction plot of CWD does not play out in this Province. Our best defence is vigilance, and cooperation between wildlife agencies, First Nation and local governments, stakeholders and the communities most likely to be affected.

Hunters Note. Although CWD is not known to affect humans, the meat should not be eaten. Suspect animals or carcasses should be reported to the BC Wildlife Health Program (250 751-3219 or the RAPP line 1-877-952-8277). When processing a suspect animal, hunters should take care to avoid direct contact with the animal’s body fluids and especially the brain, backbone or internal organs. Avoid sawing through any bones by separating the carcass at the joints. Leave the high-risk body parts behind.