When you read the word “wolverine”, what comes to mind? A snarling, snapping North-American version of the Tasmanian devil? A fearsome furball taking down prey ten times its size? Hugh Jackman?

For a creature whose reputation has reached mythical proportions, it might surprise you to learn that there’s still a lot we don’t know about wolverines. Naturally rare, wolverines are found in remote wilderness areas, making them challenging study subjects. But with increasing pressure on the landscapes that wolverines and other wildlife call home, it’s more important than ever for land managers to have accurate information on wolverine populations in BC. Advances in research techniques and technology are not only providing the data necessary to protect wolverines, they’re actually changing the way we view this elusive species.

Cliff Nietvelt is a BC government wildlife biologist who has been studying wolverines since 2009. It was that year, working on a collaring project in the North Cascades, that he had his first up-close encounter with a wolverine. “We had set up a box trap and caught other carnivores but had no luck getting any wolverines,” recalls Cliff. “I’d actually gone out to close the trap for a few days when I noticed a wolverine track. I tapped on the top of the box and heard this low, guttural growl, the kind that makes the hair stand up on the back of your neck.” The wolverine – nicknamed “Rocky”- was fitted with a satellite collar and sent on his way to collect information about the species’ habitat use and range.

Now, Cliff has just completed another wolverine conservation project supported by the Province and the Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation. Using a combination of remote cameras and genetic analysis, the project examined how wolverine distribution and density could be affected by factors such as human disturbance. This question is of particular importance in the South Coast region of BC – a paradox of development and wilderness.

“Here, we have the bulk of BC’s human population and Canada’s third largest metropolitan centre adjacent to this really rugged terrain that’s home to grizzly bears, mountain goats, wolverines – all species with big space requirements,” says Cliff. “It’s good habitat for the most part, but it’s becoming more and more fragmented by roads and human habitation.”

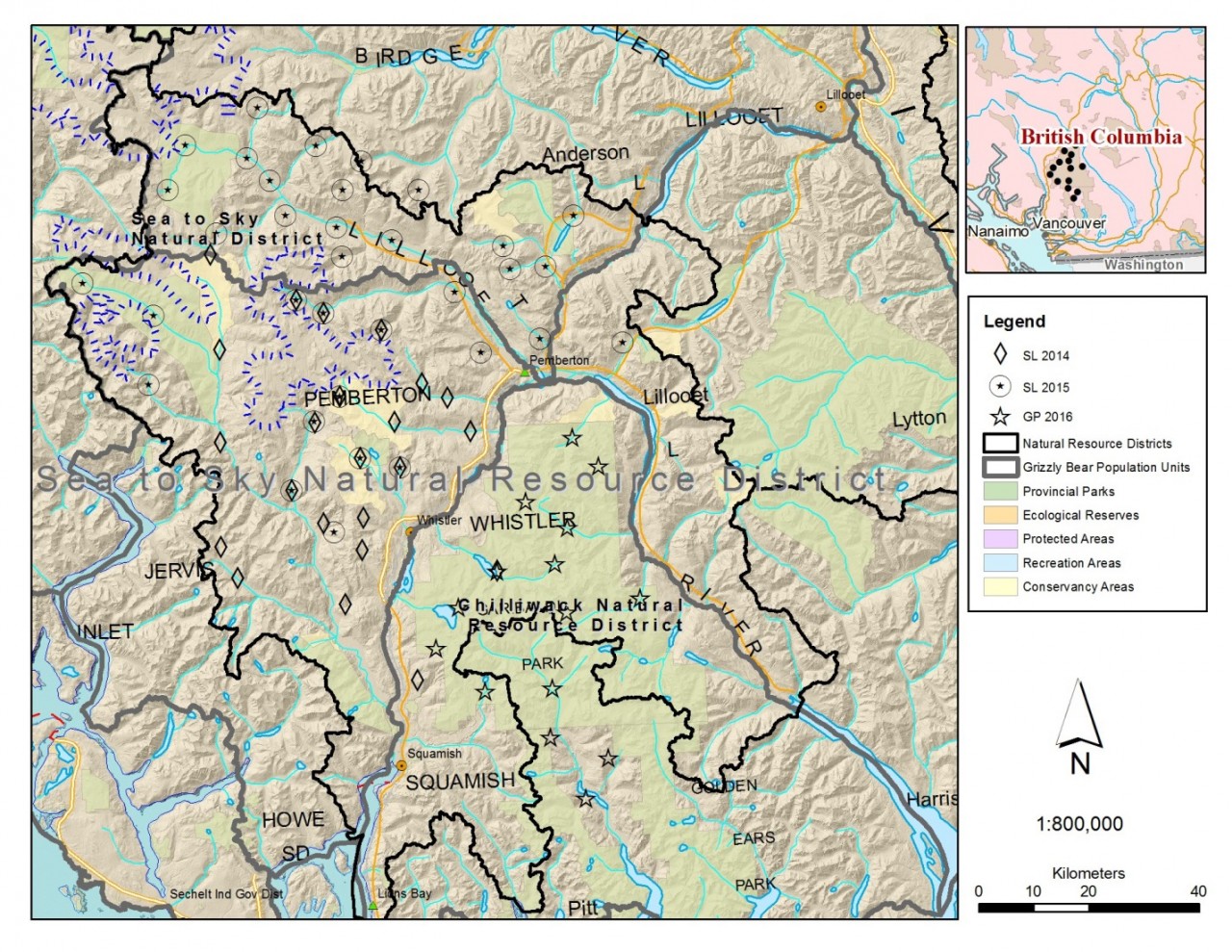

Cliff and his team set up over 70 data collection sites in the South Coast’s Sea-to-Sky District. Each site was equipped with a remote camera, a run-pole and specially-designed hair snaggers made from alligator clips and barbed wire. The setup was based on research done in Alberta and Alaska, but the BC team had to customize some of their techniques to meet the unique challenges posed by West Coast weather.

Cliff and his team set up over 70 data collection sites in the South Coast’s Sea-to-Sky District. Each site was equipped with a remote camera, a run-pole and specially-designed hair snaggers made from alligator clips and barbed wire. The setup was based on research done in Alberta and Alaska, but the BC team had to customize some of their techniques to meet the unique challenges posed by West Coast weather.

To attract wolverines to the site, they started with a “lure”: a tantalizing mix of beaver castoreum, marten or fisher musk, and essence of skunk. “We mix it all up in a 2L milk jug with a glycerin base,” explains Cliff. “It’s pungent at first, but it loses its potency fairly quickly in wet conditions.” To offset this, the team had to bring in an extra ingredient tolerated by only the toughest of researchers: rotten cattle blood.

“The cattle blood was primarily used for grizzly bear DNA stations and sourced from a local abattoir. We have to keep it at the local dump, where it’s stored in barrels, baking in the sun. After a few months, it gets quite the bouquet on it. Ninety-nine percent of people who’ve experienced it vow never to touch the stuff again,” shares Cliff. “We splash it on the trees in the periphery and it mimics a kill site or rotting carrion. Even a couple of weeks later, the scent of blood will still be in the air. It draws the animals close enough to spot the bait. We primarily use beaver meat, as we can source it from local trappers. But we’ll also use road-killed moose, elk and deer when we can get it.”

Like the lure, Cliff’s description of bait preparation is not for the squeamish. “We have to freeze it solid first so we can easily cut it up with a chainsaw, and we need to be able to drill through bone to hang it at the site. Otherwise, an animal can rip it off pretty quickly.” If the bait disappears, Cliff says it doesn’t take long for the animals to stop coming, and this impacts the effectiveness of the study. “You risk underestimating what’s out there. To mitigate this, we hang a cattle femur at each site, as it serves as a visual attractant and wolverines can also break the bone to access to marrow. If there’s at least a bone still hanging, you’ll still get wolverines coming to check it out and chew on it.”

To reach the bait, wolverines make their way across the run-pole, a platform of sorts constructed from two 4x4s braced to a tree. At the end of the 4x4s is a reinforced plastic frame attached to a 2×4 cross piece, and behind this are two plastic rods with a carefully arranged series of alligator clips with jaws open in wait. As the wolverine vigorously attempts to take down the bait, they knock the alligator clips shut and leave a hair sample behind. This technique works well for matching a wolverine caught on camera with its DNA from the hair sample, but an additional modification had to be made after the team found they had multiple wolverine visitors. “The disadvantage of the alligator clips is that they usually only collect hair from one animal, so if there are three or four wolverines in a sampling session, you’re not collecting the hair from all of them,” explains Cliff. “So we found a way to add barbed wire to the tree and run-pole. We’ve really refined it to the point that we’re getting much better samples from the wire than the alligator clips.’”

To reach the bait, wolverines make their way across the run-pole, a platform of sorts constructed from two 4x4s braced to a tree. At the end of the 4x4s is a reinforced plastic frame attached to a 2×4 cross piece, and behind this are two plastic rods with a carefully arranged series of alligator clips with jaws open in wait. As the wolverine vigorously attempts to take down the bait, they knock the alligator clips shut and leave a hair sample behind. This technique works well for matching a wolverine caught on camera with its DNA from the hair sample, but an additional modification had to be made after the team found they had multiple wolverine visitors. “The disadvantage of the alligator clips is that they usually only collect hair from one animal, so if there are three or four wolverines in a sampling session, you’re not collecting the hair from all of them,” explains Cliff. “So we found a way to add barbed wire to the tree and run-pole. We’ve really refined it to the point that we’re getting much better samples from the wire than the alligator clips.’”

In total, Cliff’s study collected 1,560 hair samples in the Squamish-Lillooet and Garibaldi-Pitt regions. The DNA from these samples was analyzed in the lab and determined to belong to 36 different wolverines (20 males and 16 females), and as many as 45 wolverines were identified visually. While the number of individuals was higher than expected, it was the degree of genetic isolation between the geographic populations that the lab described as “remarkable”. After incorporating the results of hair samples from a separate wolverine study in the Bridge area, the lab found there is almost no mixing of individuals between the 3 regions: the populations are almost completely distinct. Not only is it highly unusual to find such clear separation between populations in an area of this size, it also has important conservation implications. “Isolated populations are much more susceptible to any kind of disturbance or mortality,” says Cliff. “And if they’re wiped out, there’s a much lower chance of an area being recolonized.”

With the rapid pace of development on the South Coast, Cliff feels there’s cause for concern. “You’re dealing with a species that’s likely not as tough as we think, and maybe not as resilient as we think,” he says. “Because of the [remote] cameras, we’re getting a very different picture of wolverines.” While the cameras’ primary role in Cliff’s research is to match up an individual wolverine’s unique throat and chest markings with the genetics from the hair samples, they also act as a fantastic window into the secret world of wolverines. Multiple clips show wolverines playing and socializing with each other, and Cliff’s study has identified up to six different wolverines visiting a particular site. It would seem that wolverines (on the South Coast, anyway) are hardly the reclusive loners they’re reputed to be. The footage also shows a side of wolverines that is far more vigilant than vicious. Even when engrossed in a meal of beaver bait, the animals frequently pause to look, listen, and smell, behaving more like prey than predator. While there’s no doubt that wolverines can be fierce hunters, they are not fearless, and seem easily spooked by the presence of other predators – and humans.

“We see higher detection rates of wolverines at sites that are truly backcountry, with no human access,” explains Cliff. “Sites in the front country that are adjacent to snowmobile trails and the like have a much lower rate of detection.” Development and a reduced snowpack caused by climate change could result in increased access to areas where wolverines have traditionally lived undisturbed. Increased access could also lead to increased competition from wolves and coyotes in habitats that were formally a niche for wolverines. Neither scenario bodes well for the species.

“If you look at where wolverines are found, they are true wilderness areas,” says Cliff. “In places such as Ontario, the range of wolverines has decreased over 50% since 1850, and now they are only found in the province’s far north. In BC, we have the advantage of very rugged terrain that, thus far, has been difficult to access.” Cliff says the real importance of this research is to get a clear understanding of what factors are important to wolverine survival, so that we can work to protect them before the damage is done. The benefits are likely to go far beyond saving the South Coast’s wolverines. Cliff explains: “I have this saying: If we protect wildness, we protect wilderness. The wolverine is a species that is representative of wildness, and if we can keep species such as wolverine on the landscape, we can BC help maintain BC’s wilderness that so many British Columbians hold dear.”

You can watch a video of footage from this project here.