The following stroy was published in the 2013 July/August issue of Outdoor Edge magazine.

On July 24, 2007, construction workers punctured a pipeline in Burnaby, sending crude oil spraying 12 metres into the air. The black geyser flooded surrounding homes and oil poured into the storm sewers, eventually making its way to the waters of Burrard Inlet. The spill impacted over 1200 m of shoreline, contaminating birds and sea life.

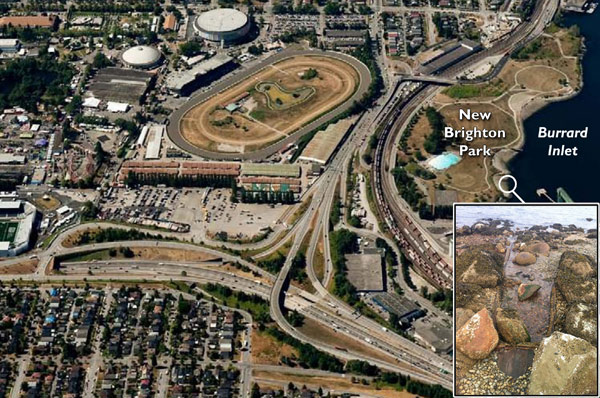

In addition to the estimated $15 million that was spent on cleanup and rehabilitation, the convicted parties agreed to pay a total of $447,000 to the Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation (HCTF) as part of the Crown Counsel’s recommendation to use creative sentencing provisions in the Environmental Management Act. Creative sentencing provides an alternative to traditional sentencing options (such as fines or imprisonment) by allowing judges to specify payments be made to HCTF. In this case, the creative sentencing award allowed HCTF to form the Burrard Inlet Restoration Project, an innovative granting program providing funding for restoration projects on the Inlet. The first application intake provided funding for 6 projects, all of which involve students of BCIT’s Ecological Restoration program. I had the opportunity to speak with three of those students: Sarah Nathan, whose plan to daylight a creek in New Brighton Park will restore historical cutthroat trout habitat, and Michelle Holst and Deanna MacTavish, who are working together to return Mosquito Creek Estuary to an ecosystem capable of sustaining a variety of species.

Q. One of the reasons we decided to write this story is because the BCIT Burrard Inlet presentations at the BCWF AGM were such a hit: what sort of feedback did you get from BCWF members?

Deanna: Everyone really seemed to enjoy hearing about the restoration plans. They liked that we were young people doing this work, but I think they also appreciated our commitment to these projects and this system. We’ve built long-term monitoring into our plans so that we can measure our results: determine what’s working, what could be improved upon, and apply that knowledge to other restoration projects. (Michelle and I) are even in the process of forming a Society, which will focus on improving survivorship of salmonids and other aquatic species in degraded estuaries within Burrard Inlet.

Q. Speaking of degradation, tell me about your project sites: what environmental concerns do your restoration plans address?

Q. Speaking of degradation, tell me about your project sites: what environmental concerns do your restoration plans address?

Deanna: Mosquito Creek is a highly-impacted estuary. It’s had a substantial amount of development occurring on it over the past 80 years, and it’s mostly concrete. There’s no refuge or nutrients for fish or other aquatic species, so we plan to introduce complexity by adding vegetation, coarse woody debris, and terracing down some of the hard edges to create an intertidal habitat that’s more hospitable to fish and humans alike.

Sarah: At this point, Renfrew Creek is almost completely underground: it’s one of many streams around Vancouver that were infilled. Once the daylighting is complete, water quality will be the big challenge: we’re right by Highway 1, so everything that gets on the road will essentially get flushed into this system. We will be doing stormwater monitoring in the fall to find out what kind of improvements need to be made so that the stream can support cutthroat. They’re very sensitive to shifts in water quality: Reeves et. al. (1997) likened them to “canaries in a coal mine”.

Q. Deanna, the Mosquito Creek plan also emphasizes cutthroat, but I understand you’re hoping to restore populations of other types of salmonids?

Deanna: The Squamish First Nation have told us that, in the past, they’ve seen chum, coho and rainbow trout in the estuary, but not in recent years: that’s why we’re focussing on salmonids. But this restoration has the potential to positively impact a whole range of species.

Q: The Squamish First Nation are your partners in this project. What’s it been like working together?

Michelle: Working with them has been really great. It’s a bit of a different system, and maintaining an open dialogue is key. The visuals we developed for our presentations have really helped: it’s difficult to get people to envision this kind of transformation just by talking about it. But when we show them the before-and-after images, suddenly everyone’s on the same page, excited about the possibilities… especially the elders! We are already planning training sessions to get Squamish Nation youths involved with the long-term monitoring of this site, so they can really be stewards of their own land.

Q. In addition to partners, both of your projects involve working with multiple stakeholder groups. Is it difficult trying to incorporate so many different viewpoints?

Sarah: Yes! New Brighton Park (where Renfrew Creek will be daylighted) has so many different user groups: dog walkers, birdwatchers, anglers wanting a catch-and-release fishery, it’s a real challenge trying to incorporate all of these (sometimes conflicting) uses into a plan that will keep everyone happy.

Michelle: Unfortunately, there can be a real disconnect in communications between stakeholders: industrial, commercial, residential, First Nations, municipalities, government… sometimes we’re arguing the same thing, just in different languages. That’s part of the impetus for forming this Society: to act as a mediator and get everyone working together.

Q: With all the environmental pressures and habitat modification resulting from decades of intense development on the Inlet, can we really hope to maintain the ecological integrity of this ecosystem? How do we move forward?

Michelle: I think we need to find a balance between accepting that development on the Inlet inevitable: populations are growing, industry is growing, and we require resources, but we don’t have to just take. We can develop new methods to coexist with nature and try to offset some of the impacts that development has.

Sarah: People look at these very disturbed areas and think there’s no point in even trying, and I think one of the big challenges is showing people that it is possible: with a little funding, it can work.

Q. How important is the funding from HCTF to projects such as these?

Sarah: This grant money is crucial: even though we’re partnered with the City, environmental projects tend to be a lower priority when budgets are tight. Without outside funding, they might not happen at all. We’re always looking for more partners, and the money from HCTF will hopefully help in leveraging additional funds.

Q. What would you say to potential partners to convince them these projects are a worthwhile investment?

Sarah: Because these sites are located in such urban areas, they have a huge potential to increase public awareness about the importance of streams and estuaries. Renfrew Creek is in a popular park, right next to a swimming pool and in close proximity to the PNE grounds: what a great audience for the work being done! In Vancouver, around 120 creeks that were historically good cutthroat habitat have all been paved over as part of urbanization, and likely a number of those could be daylighted. I hope that successfully completing these initial projects will give us the support we need to restore other creeks and estuaries, and that would be a really good thing for people and salmonids alike.

Read more about HCTF’s Burrard Inlet Restoration Pilot Program>>