There are a lot of great fishing lakes located in the Southern Interior region of BC. Ideal water chemistry, long, hot growing seasons and managed populations of stocked rainbow, brook trout and kokanee provide a diversity of angling experiences. A quick look at a map of the Merritt, Logan Lake and Kamloops area will reveal just how many small lake fisheries are waiting to be fished. One of the most popular groups of stillwaters is those found within the Tunkwa Lake watershed. They include Tunkwa, Leighton, Morgan and Six Mile lakes. Each year over 30,000 angler days are spent plying these waters in search of rainbow trout. Recreational fishing within this watershed has been a popular pastime for over 70 years. Tunkwa Lake Resort has been in operation for over the past 40 years and in 1996 Tunkwa and Leighton lakes were the cornerstones of the newly created Tunkwa Lake Provincial Park.

The development of the recreational fisheries within the Tunkwa watershed was in large part the result of creek diversions and construction of dams on key lakes in an effort to store and supply water for downstream agricultural purposes. Some of the original irrigation works done by pioneering ranching families date back to the late 1800s. Those initial diversions and dams provided enough additional water in Tunkwa Lake to support fish life. The first recorded government stockings of Tunkwa date back to 1939. Those first stockings produced some amazing fish and fishing action. However, over the years, the demand for water increased as more land was cleared and put into forage production. Years with a good snowpack combined with adequate rainfall during summer months meant good survival of trout in both Tunkwa and Leighton lakes. Conversely, low snowpack and summer drought conditions would result in more winterkills and summerkills.

Over the past 75 years, there have been a lot of physical improvements made to the dams, diversions and water delivery systems that have made these lakes what they are today. Perhaps the most significant enhancement project in the Tunkwa watershed began in 1994 when the Provincial Ministry of Environment completed a study of the watershed of water use and availability while considering ways to optimize the use of water to benefit fish, wildlife and agricultural interests. During the same time period, the ownership of Six Mile Lake Ranch near Savona changed hands. A large portion of this cattle and alfalfa production ranch was being redeveloped into a golf course and housing complex. During the government approval process, the province was able to obtain some of the Six Mile Ranch water rights. Converting these water licences from irrigation to conservation use was key to allowing much of the planned watershed enhancement work to move forward.

Ongoing discussions began with other user groups within the Tunkwa watershed as all had a stake in ensuring their licenced water was protected while at the same time realizing that water conservation improvements would benefit all users. Individual ranchers, the Durand Creek Water Users Community, government agencies, First Nations, Ducks Unlimited and member clubs of the BC Wildlife Federation worked cooperatively to realize the goals of the watershed enhancement plan.

The biggest obstacle to making this plan work was seeking out appropriate funding sources. The Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation proved to be the perfect fit for this project. The origins of this not for profit foundation started with anglers, hunters, trappers and guide-outfitters, who were willing to pay more for licensing fees if this extra funding resulted in enhancements to fish and wildlife populations and the protection of important fish and wildlife habitats. Members of the BC Wildlife Federation were a major push behind this initiative. In 1981 the BC government established the Habitat Conservation Fund, whose revenues would be collected through surcharges on fishing, hunting and trapping licenses. The goal of the fund was to partner with individuals or groups to deliver projects that restored, enhanced and increased fish and wildlife habitat in the province. In 2008 HCTF received charitable status and the current name of Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation was established.

Beginning in 2001, the provincial Ministry of Environment began applying for funds from the HCTF. The Ministry partnered with Ducks Unlimited Canada to further leverage funds for the improvement of both lakes and wetlands within the project boundaries. Over the next 5 years, almost $350,000 was spent on water conservation projects within the Tunkwa Lake watershed. This work included rebuilding the existing diversion and control structures, new dam construction and rebuilding of both dams on Tunkwa and Leighton lakes. An additional 11 wetland basin improvement projects were constructed in the upper end of the Tunkwa watershed. These newly created wetlands provided habitat not only for waterfowl but also a wide variety of birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians.

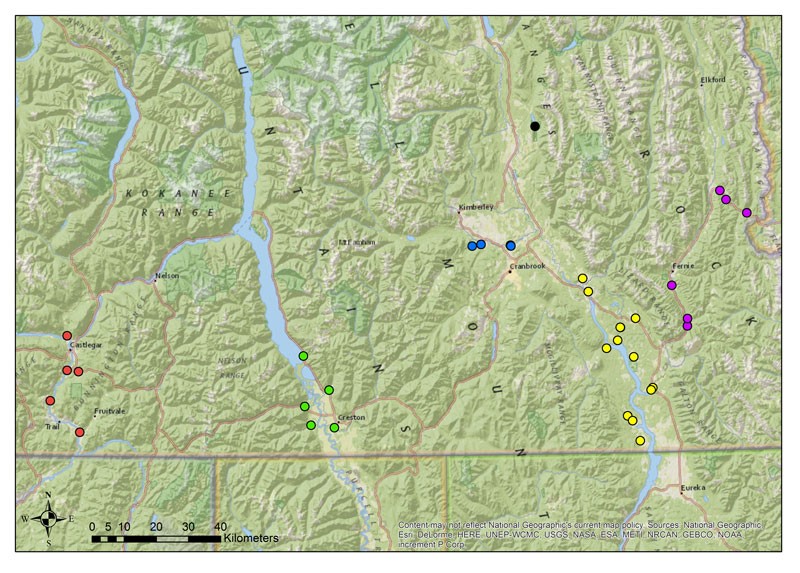

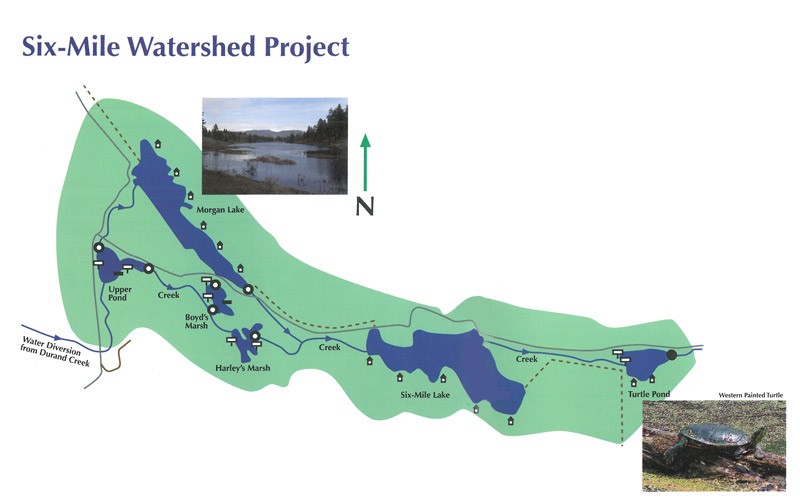

Water licencing now owned by the provincial fisheries program was used for conservation purposes to develop Morgan Lake, which historically was a small pond that laid alongside the old Trans-Canada Highway, just east of the town of Savona. It was a fishless waterbody that had tremendous potential to support fish life with increased water levels. HCTF funds were used to build a dam at the east end of the lake, and water from Durand creek (which originated at Tunkwa and Leighton lakes) was used to fill the basin. At completion, almost 5 meters of water was added to the original basin, creating the new Morgan Lake. The lake now had a maximum depth of over 10 meters and could definitely sustain fish life. An open ditch was constructed to deliver water from Morgan to nearby Six Mile Lake to allow seasonal flushing and filling of water. Water that eventually reached Morgan and Six Mile lakes arrived by a newly constructed 6 km long open ditch that diverted water from Durand Creek. The dam on Six Mile Lake was also rebuilt and a small sheet pile weir dam was installed on Turtle Pond, which lies just east of Six Mile Lake. This is an important waterfowl nesting and migration wetland. Several other smaller wetland ponds were created using this new water from Tunkwa and Leighton lakes. Upper Pond, Boyd’s Marsh and Harley’s Marsh lie just south of Morgan Lake and all receive water via the Durand Creek diversion ditch.

In all, 15 wetland habitats making up a total of 280 ha were created within the Tunkwa watershed. The additional work of rebuilding or constructing new dams, diversion structures and delivery channels significantly increased the ability to deliver water efficiently while at the same time conserving water for fish, wildlife and agricultural uses. HCTF continues to contribute $12,000 annually for the operation and maintenance of structures built within the watershed.

So how are the trout fisheries in these 4 lakes doing some 16 years after the initiation of this project? Tunkwa and Leighton lakes continue to be very popular fisheries, no doubt aided by the fact that there are two large campgrounds and a thriving resort operation within this provincial park. Tunkwa and Leighton lakes are back to being stocked with Pennask rainbow trout after almost a decade and a half of being augmented with Blackwater rainbows. Fishing success continues to be good on both lakes and a public fishing dock located on Tunkwa Lake has proven to be a very popular addition to the park. Both lakes are also open to ice fishing which has allowed even more anglers to enjoy these resources.

Morgan Lake continues to be a great success story. Since its creation, it has been managed as a catch and release fishery that is stocked annually with both Blackwater and Fraser Valley strains of rainbow trout. Both strains reach in excess of 5 lbs. The lake is quite popular in the early spring, as it and Six Mile Lake are generally the first lakes to become ice-free each year. Six Mile Lake has a long history of being a great spring and fall fishery and is very popular with local anglers. It is also stocked with both Blackwaters and Fraser Valley rainbows. Both lakes provide anglers with a backdrop of sagebrush and grassland vistas along with consistent fishing action.

The funding made available through the Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation was instrumental in making all this enhancement work possible. Partnering with Ducks Unlimited Canada strengthened not only the financial end of this project but also helped ensure existing wetlands were enhanced and new ones were created to the benefit of many species of wildlife. In the end, recreational users and the agricultural community continue to benefit from more effective management of the water resources within the watershed.

The next time you purchase your fishing or hunting licence, remember that you’re helping to fund conservation projects like this one. To date, HCTF has invested over 165 Million dollars in fish and wildlife projects in BC. To find out more about conservation projects happening in your community, take a look at HCTF’s interactive project map.

Brian Chan has been fortunate enough to live and work for the past 35 years in Kamloops, British Columbia. It is here that Brian, as a provincial fisheries biologist, managed the recreational stillwater trout fisheries in the Thompson/Nicola Region, and developed his fishing skills. Brian’s lifelong passion for fly fishing has resulted in his spending literally thousands of angling days on these world class waters. He has shared his extensive knowledge of aquatic biology, trout ecology, entomology, and lake fly fishing tactics with others, through magazine articles, books, and instructional DVDs. Brian has been featured on many TV fishing shows and is currently a regular guest on Sport Fishing on the Fly and co-host of The New Fly Fisher.