The following story was submitted to us by Berry Wijdeven, a biologist working on HCTF project 6-235, Juvenile Sooty Grouse Dispersal and Winter Survival on Haida Gwaii. Berry works for the Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations (MFLNRO) as the Species at Risk Coordinator for Haida Gwaii.

The radio receiver, though dialed way down, squeaks loudly, insistently. Somewhere, within 10 meters or so, a radio collared female grouse is hiding. Possibly nesting. We want to find that nest and put a camera near it to see whether the chicks fledge successfully or whether the nest fails. But we don’t want to disturb the bird, potentially flush her off her eggs, so we proceed with great caution. The radio signal originates from a nearby stump, which is surrounded by a dense growth of salal. Entering that growth would surely alarm the grouse, so here we stand, hoping to catch a glimpse of a bird that is likely watching us.

Inventory studies have suggested that the number of Haida Gwaii Sooty Grouse has declined substantially. That’s a problem for the grouse population, but also of concern to the Northern Goshawk, a species listed as threatened, which is having a tough go of it on Haida Gwaii, and for whom grouse is a major prey item. Figuring out why the grouse population has declined could help manage both species.

Thanks to a partnership including MFLNRO, Haida Gwaii District and Coast Area Research, Parks Canada and the Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation, we have been studying grouse for the last three years, looking at habitat use, seasonal movement, juvenile dispersal, survival rates and causes of mortality. As part of this research, we are monitoring nesting success where motion detection cameras have proven to be a cost-effective method of determining what happens at the nest site. But first we have to find the nests. Over the last three years, we have caught some 70 female grouse and equipped them with radio transmitters, each with their own radio frequency. We monitor these transmissions year round to see where the birds are and what habitat they use.

Grouse move between breeding and winter home ranges, so in spring, we increase our monitoring efforts to pinpoint their breeding home range. When the signal stops moving through the landscape, it could indicate that the female has started to nest. For our research, we have chosen an area which is dissected by logging roads, which makes getting around the rugged Haida Gwaii landscape somewhat feasible. Sometimes the hens are kind enough to locate their nest close to one of those roads. At other times we are not so lucky, and a serious crosscountry slog is required. Cedar stands with boggy soils and chesthigh salal stands which suction your boots or tangle them in a web of branches remain my favourite hiking destination. As we follow the radio signal through the forests, trying to compensate for signals bouncing off trees, hills and rocks, we become increasingly vigilant, for the birds have some creative methods to hide their nests.

Grouse are the Rodney Dangerfield of the bird world, often getting little respect. Stupid and tasty are the two adjectives heard most often when discussing grouse. Truth be told, people generally don’t pay much attention to a grouse they see them standing by the side of the road, or worse, in the middle of the road. But once you see a mother hen, mostly defenceless, guard her chickens throughout the summer from a multitude of dangers, you start revisiting your thoughts on grouse, and what she is potentially guarding as she stands motionless in the middle of that road.

Up close grouse are beautiful birds, with delicate and intricately patterned feathers. Males, generally a dark blue, puff themselves into magnificent creatures during the mating season, showing off their bulging yellow air sacks, fanned tail and (when inflated) orange combs. Their size and appearance at this time of year contrasts sharply with their usual look and provide a rare splash of colour amongst the multitude of forest greens.

But it’s a hen we are trying to locate, and the females, mostly shades of brown, are blessed with impressive camouflage. We circle the salal, trying to determine from which side the radio signal is strongest, but fail to determine the bird’s location. So we stand there, staring intently at the growth. And then we see something, through a small opening between some leaves. An eye. Staring back at us just as intently. There she is! We quickly determine that the hen is indeed nesting, note the location and deploy the camera. Then we retreat, leaving the grouse to do her thing. Hopefully she’ll be successful in fledging her young. We’ll see.

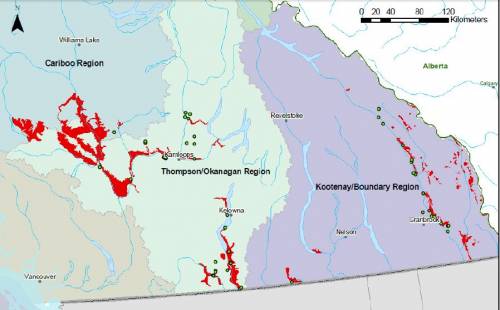

In the Telkwa Mountains near Smithers, BC, a small herd of Mountain Caribou persists after nearly disappearing from these ranges only two short decades ago.

In the Telkwa Mountains near Smithers, BC, a small herd of Mountain Caribou persists after nearly disappearing from these ranges only two short decades ago. The recreation portion of the study will incorporate citizen science, asking locals participating in activities such as snowmobiling, backpacking and backcountry skiing to use hand-held GPS units to record the location of their activities. Data collected from these volunteers and the collared caribou will help researchers determine the relationship between herd and human activity. Project leaders hope that involving local user groups in data collection and management techniques will inspire ongoing stewardship by participants. Already, the Smithers Snowmobile Association has created a page on their website providing updates on the location of collared caribou so their members can avoid disturbing them. Ideally, the result of this research will allow for development of a solution that provides protection for the caribou while still allowing opportunities for winter recreation.

The recreation portion of the study will incorporate citizen science, asking locals participating in activities such as snowmobiling, backpacking and backcountry skiing to use hand-held GPS units to record the location of their activities. Data collected from these volunteers and the collared caribou will help researchers determine the relationship between herd and human activity. Project leaders hope that involving local user groups in data collection and management techniques will inspire ongoing stewardship by participants. Already, the Smithers Snowmobile Association has created a page on their website providing updates on the location of collared caribou so their members can avoid disturbing them. Ideally, the result of this research will allow for development of a solution that provides protection for the caribou while still allowing opportunities for winter recreation.