Clearcutting continues to be the dominant harvesting system across much of North America. Its environmental impacts have long been the subject of debate, but there’s a general consensus that this forestry practice results in a shift in the species inhabiting an area. In the years following a clearcut, grasses and shrubs thrive, providing browse for moose and deer. However, this short-term boon comes at the expense of some of the site’s previous residents. Furbearers such as weasels and marten depend on mature forest, both for concealment from predators and for den and rest sites in the form of coarse woody debris. On most clearcut sites, this debris is burned after harvest. But what if there was a way to prevent the displacement of some forest-dependent species by building habitat out of waste wood instead of burning it?

We spoke with Dr. Thomas Sullivan of the Applied Mammal Research Institute about his HCTF-funded project examining whether windrows constructed out of waste wood could reduce some of the negative impacts of clearcutting on small mammals.

HCTF: I understand that many furbearers are reliant on mature forest habitat, and will inevitably be impacted by clearcutting. Would you say your project is about making the best out of an imperfect situation for these species?

Sullivan: Yes: the overall goal here is to try and make these harvested sites more amenable to small mammals, particularly weasels, marten, and their primary prey species, red-backed voles. Marten in particular dislike the openings left by clearcuts, because they leave them vulnerable to predation by hawks and owls. As these openings continue to increase in size, we have to provide these animals some way to get from one section of uncut forest to another if we want to keep them on the landscape.

Sullivan: Yes: the overall goal here is to try and make these harvested sites more amenable to small mammals, particularly weasels, marten, and their primary prey species, red-backed voles. Marten in particular dislike the openings left by clearcuts, because they leave them vulnerable to predation by hawks and owls. As these openings continue to increase in size, we have to provide these animals some way to get from one section of uncut forest to another if we want to keep them on the landscape.

HCTF: For this project, you proposed that waste wood shaped into windrows could act as travel corridors for small mammals, allowing them to move across clearcuts to areas of intact forest. How did you test this idea?

Sullivan: We used a combination of live traps, scat analysis and predation events to compare small mammal presence in windrows constructed out of post-harvest woody debris to their prevalence on clearcuts where the debris was left distributed, both on sites near Golden and Merritt. What we found was that evidence of marten, weasels and red-backed voles was consistently higher in the windrows.

HCTF: Your results seem to support the idea that the relatively small labour investment required to construct windrows out of post-harvest woody debris could pay big dividends for wildlife, yet the majority of this debris is burned. Why?

Sullivan: Currently, foresters are legislated to deal with post-harvest woody debris: they have to get rid of it, either by burning or having someone agree to come and chip it up for biofuel feedstocks, with the latter only being feasible on sites near roads and processing plants. To my knowledge, the only way around this legislative requirement is if you build a variance into your silviculture prescription stating that you are going to leave some piles or windrows for habitat.

Sullivan: Currently, foresters are legislated to deal with post-harvest woody debris: they have to get rid of it, either by burning or having someone agree to come and chip it up for biofuel feedstocks, with the latter only being feasible on sites near roads and processing plants. To my knowledge, the only way around this legislative requirement is if you build a variance into your silviculture prescription stating that you are going to leave some piles or windrows for habitat.

HCTF: What is the reasoning behind the current requirements around debris removal?

Sullivan: [The debris is considered] a fire hazard, even though there is absolutely no scientific evidence that these piles catch on fire by themselves. Once in a blue moon, up on a hilltop, you might get a lightning strike, but if there are any trees around, it’s far more likely to hit them. Any actual fire risk comes from humans who’d set them ablaze, which is why we probably don’t want to build windrows on sites near main roads. Far better to build them along deactivated roads or in the back country – and there’s certainly no shortage of this type of cut area. Before we can make windrows standard practice on these types of sites, there has to be a change in government policy, and that could take some time. I believe policy revisions have to follow what’s happening on the ground: we need to get as many foresters and companies trying out this method, even if it means going through a laborious variance process.

HCTF: Speaking of foresters, both Louisiana Pacific Corp. in Golden and Aspen Planers Ltd. in Merritt helped fund this study, along with HCTF. In the course of doing research on the effects of clearcutting on small mammals, have you found a significant difference in the effort that individual forestry companies are willing to expend to preserve wildlife habitat?

Sullivan: You know, the individuals are crucial. The silviculturalist with Louisiana Pacific in Golden has been instrumental in thinking in a broad-minded way. He is interested in anything that they can do to make the forest more diverse. Initially, this began as a business concern: he had a serious problem with the Microtis species of voles (the meadow voles and long-tailed voles) feeding on newly-planted trees, so he was very interested in anything that would increase the number of predators on his clearcut units.

HCTF: So building windrows to enhance predator habitat could be advantageous for foresters, as well as ecosystems?

HCTF: So building windrows to enhance predator habitat could be advantageous for foresters, as well as ecosystems?

Sullivan: Definitely. If you’ve got Microtis voles in your harvest area, it can be a serious problem. They’ll eat many of the seedlings – enough to necessitate replanting. There’s been a lot of work put into preventing the damage done by these species. Re-creating habitat to help maintain predator populations seems a logical solution.

HCTF: What about cases that are not so mutualistic: is there an appetite within the industry to adopt practices that conserve biodiversity, even if they don’t provide direct business benefits?

Sullivan: I think so, but again, it is company- and even individual- specific. For example, at Elkhart (our study site near Merritt), Aspen Planers have provided financial and in-kind support for this research, and they don’t have a problem with voles damaging trees. They are simply interested in what they can do to improve wildlife diversity. Again, this could be attributed to certain individuals’ philosophies, though I would say that the company policies of both of Aspen Planers and Louisiana Pacific are pretty positive in this direction.

HCTF: In one of your recent studies, you suggest that a habitat credit system, similar to current carbon offsetting programs, might provide the financial incentive necessary to encourage companies who are perhaps less-ecologically inclined to change their current practices. Can you elaborate?

Sullivan: Like it or not, we are enslaved by economics. The concept of assigning a dollar amount to ecological values leaves a bad taste in some people’s mouths, but I think we need to move there. Whether we call them habitat credits or biodiversity credits, it’s really about finding a way to recognize the importance of wildlife and habitats in an economically-driven system. We think of biofuel feedstocks as products from woody debris, why not small mammals?

Sullivan: Like it or not, we are enslaved by economics. The concept of assigning a dollar amount to ecological values leaves a bad taste in some people’s mouths, but I think we need to move there. Whether we call them habitat credits or biodiversity credits, it’s really about finding a way to recognize the importance of wildlife and habitats in an economically-driven system. We think of biofuel feedstocks as products from woody debris, why not small mammals?

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation invests money from angling, hunting, trapping and guide outfitting licence surcharges into conservation projects across BC. You can read more about surcharge-funded projects here.

“The Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program is pleased to support this land purchase,” said Program Manager, Trevor Oussoren. “Strategic land acquisitions such as this play an important role in helping fish and wildlife for generations to come.”

“The Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program is pleased to support this land purchase,” said Program Manager, Trevor Oussoren. “Strategic land acquisitions such as this play an important role in helping fish and wildlife for generations to come.”

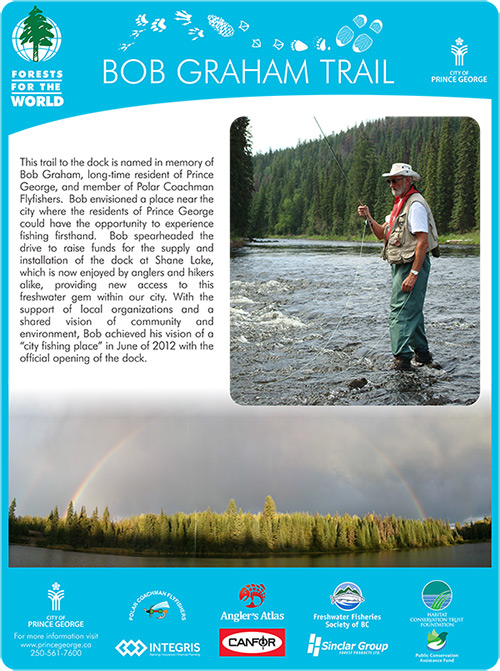

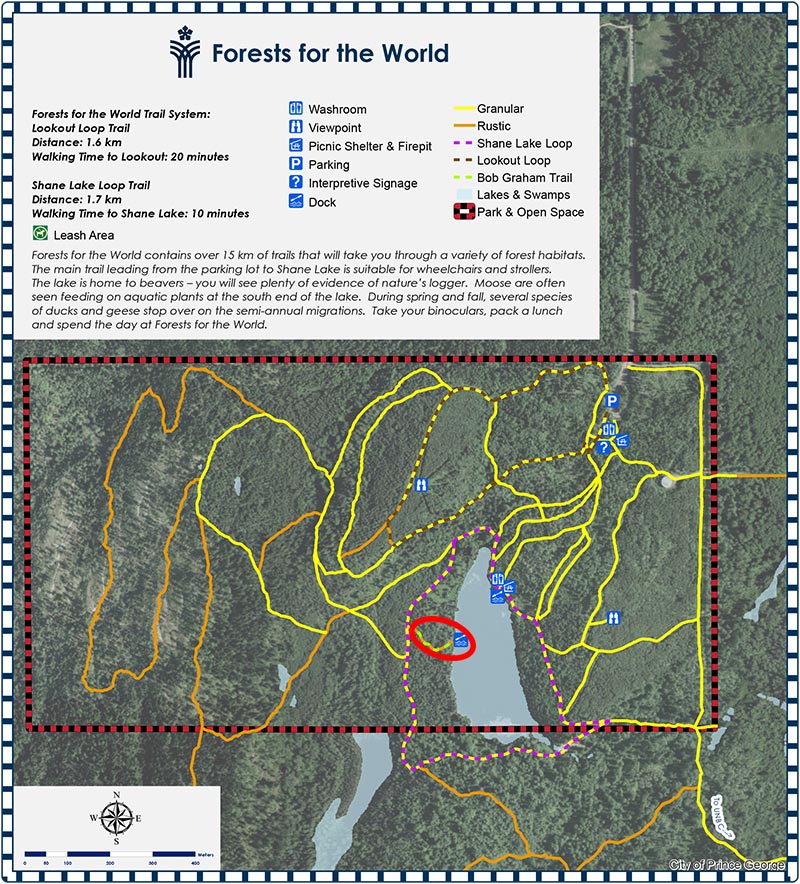

On May 8th, Prince George officials and community members gathered together with family & friends of the late Bob Graham to celebrate the naming of a new trail in his honour. The Bob Graham Trail is situated within Prince George’s Forests of the World park. The trail provides access to the fishing dock on Shane Lake, installed in 2012 as part of a

On May 8th, Prince George officials and community members gathered together with family & friends of the late Bob Graham to celebrate the naming of a new trail in his honour. The Bob Graham Trail is situated within Prince George’s Forests of the World park. The trail provides access to the fishing dock on Shane Lake, installed in 2012 as part of a

Sullivan: Yes: the overall goal here is to try and make these harvested sites more amenable to small mammals, particularly weasels, marten, and their primary prey species, red-backed voles. Marten in particular dislike the openings left by clearcuts, because they leave them vulnerable to predation by hawks and owls. As these openings continue to increase in size, we have to provide these animals some way to get from one section of uncut forest to another if we want to keep them on the landscape.

Sullivan: Yes: the overall goal here is to try and make these harvested sites more amenable to small mammals, particularly weasels, marten, and their primary prey species, red-backed voles. Marten in particular dislike the openings left by clearcuts, because they leave them vulnerable to predation by hawks and owls. As these openings continue to increase in size, we have to provide these animals some way to get from one section of uncut forest to another if we want to keep them on the landscape. Sullivan: Currently, foresters are legislated to deal with post-harvest woody debris: they have to get rid of it, either by burning or having someone agree to come and chip it up for biofuel feedstocks, with the latter only being feasible on sites near roads and processing plants. To my knowledge, the only way around this legislative requirement is if you build a variance into your silviculture prescription stating that you are going to leave some piles or windrows for habitat.

Sullivan: Currently, foresters are legislated to deal with post-harvest woody debris: they have to get rid of it, either by burning or having someone agree to come and chip it up for biofuel feedstocks, with the latter only being feasible on sites near roads and processing plants. To my knowledge, the only way around this legislative requirement is if you build a variance into your silviculture prescription stating that you are going to leave some piles or windrows for habitat. HCTF: So building windrows to enhance predator habitat could be advantageous for foresters, as well as ecosystems?

HCTF: So building windrows to enhance predator habitat could be advantageous for foresters, as well as ecosystems? Sullivan: Like it or not, we are enslaved by economics. The concept of assigning a dollar amount to ecological values leaves a bad taste in some people’s mouths, but I think we need to move there. Whether we call them habitat credits or biodiversity credits, it’s really about finding a way to recognize the importance of wildlife and habitats in an economically-driven system. We think of biofuel feedstocks as products from woody debris, why not small mammals?

Sullivan: Like it or not, we are enslaved by economics. The concept of assigning a dollar amount to ecological values leaves a bad taste in some people’s mouths, but I think we need to move there. Whether we call them habitat credits or biodiversity credits, it’s really about finding a way to recognize the importance of wildlife and habitats in an economically-driven system. We think of biofuel feedstocks as products from woody debris, why not small mammals?